It is a phenomenon that has swept the nation, seemingly coming out of nowhere in our country’s middle schools. The bewildering phrase “6-7” has been amusing kids and annoying parents for months now, but in fact, this expression dates to the 14th century and is one of modern English’s oldest.

When my 15-year-old son patiently tried to explain to me that “6-7” meant nothing, but was just something you say as a joke when you hear the numbers together, while making a weighing gesture with your hands, I asked him if it meant the same as “being at sixes and sevens?”

He didn’t know what that expression meant, and to be fair it is rather arcane. I probably read too much PG Wodehouse, but it got me thinking that maybe this “6-7” thing didn’t actually pop up out of nowhere. Maybe it is very, very old, I thought.

Turns out, that was a good instinct.

BUY YOURSELF A LIFE-SIZED T-REX AND SIX OTHER ABSOLUTELY NUTS STORIES FROM SEPTEMBER

The first usage of “6-7” dates back to the 1300s, which is about as old as modern English gets. It referred to a dice game called Hazard that would eventually develop into what we know as craps.

In the game, a player would call out the number he was trying to shoot for, or make, with two six-sided dice. Five, eight and nine were the most likely results. Six and seven, gamblers quickly discovered either through math or experience, offered lower odds and hence less chance of winning.

From then on, six and seven, taken together, became forever associated with risk and worry. It can be found in the works of Chaucer, and has marched quite steadily down through the centuries.

BOOK BUMMER: WHY READING IS IN DEEP DECLINE

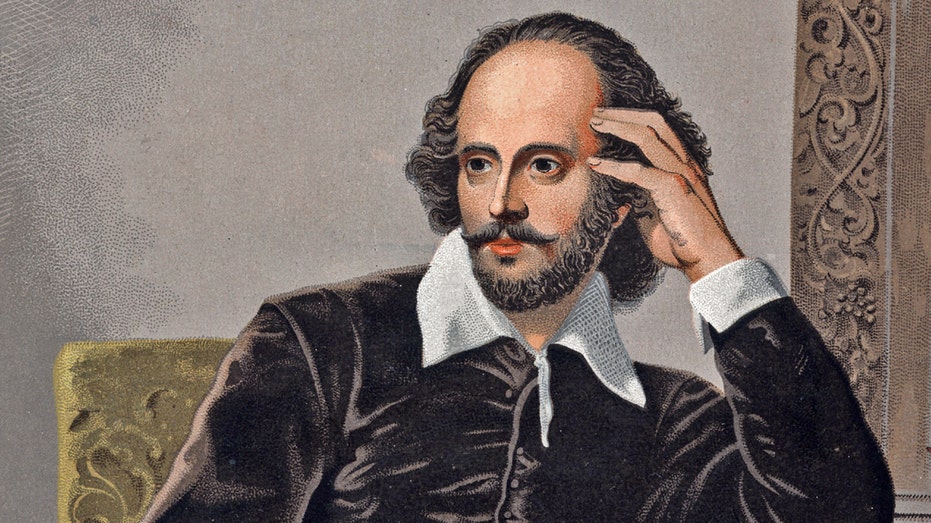

Almost 300 years later, in 1595, William Shakespeare would use the expression in his play “Richard II,” with the Duke of York uttering, “I should to Plashy too, but time will not permit. All is uneven, and everything is left at six and seven.”

Once again, in Shakespeare’s usage six and seven mean risk, worry and confusion.

Over the next few centuries, the phrase would become plural and popularized as “being at sixes and sevens,” meaning being worried or confused, as in, “My check is late and my rent is due, I am at sixes and sevens over it.”

DICTIONARY.COM DECLARES ‘6-7’ WORD OF THE YEAR

The dead giveaway that this latest iteration of “6-7” is related to its medieval precursor is the weighing motion with the hands. It says visually, “it might be this, or it might be that,” it’s confusing, unclear, a matter of chance.

What does the endurance of this symbol, this expression that has been with our native tongue since its birth really mean? What can it tell us, beyond being just a little fun fact of history?

It tells us that we are much more closely linked intellectually to those who spoke our language 700 years ago than we think, that we almost never invent, we almost always borrow or repurpose, as Shakespeare, our greatest writer, did himself.

TEST YOURSELF ON THE GEN Z SLANG OF 2025: CAN YOU DECODE ‘HUZZ’ AND ‘GLAZING’?

It was the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein who suggested that language is not merely the vessel of our thoughts, it is also the driver. Here we have the English language stubbornly demanding for centuries that these two numbers have a special meaning.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE FOX NEWS OPINION

This is why it is vital to read old books and to make kids read old books. They aren’t actually old. They are in fact, timeless in as much as their contributions become indelible. We understand what we ourselves are saying much better when we understand those who said it first.

So, the next time your kid starts giggling and saying “6-7,” just imagine them on the old-timey streets of Elizabethan London doing it, because the people there and then would know exactly what it means, even better than we do.

The history of English-speaking people is much shorter than it feels, we are much more closely related to those long gone than we recognize.

So, as we march into the future of artificial intelligence, and brave new worlds, let us remember, we find our real meaning, our real selves and what we are, in the past, not in the future, and just as with “6-7,” the past will always find a way.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM DAVID MARCUS